The helicopters arrived shortly after midday and sent a rocket hurtling into an area at the back of the crowd where children were sitting.

As people began to flee, witnesses said, heavy machine gun fire followed them.

It was the latest deadly example of how a ferocious new air campaign against the Taliban has caused a spike in civilian casualties from US and Afghan air operations.

This Afghan Air Force attack on 2 April in north-eastern Kunduz province killed at least 36 people and injured 71, the UN says. Although witnesses said Taliban fighters and senior figures were in the crowd, 30 of those killed were children. Hundreds of people had gathered outside a madrassa in the Taliban-controlled district of Dasht-e-Archi to watch a group of students have turbans tied around their heads in a traditional ceremony to recognise their memorisation of the Holy Quran.

“I saw turbans, shoes, arms, legs and blood everywhere,” one local resident told the BBC the next day, describing the aftermath. Everyone in the area knew the event was happening, and many children, he said, had turned up for the free lunch that was about to be served.

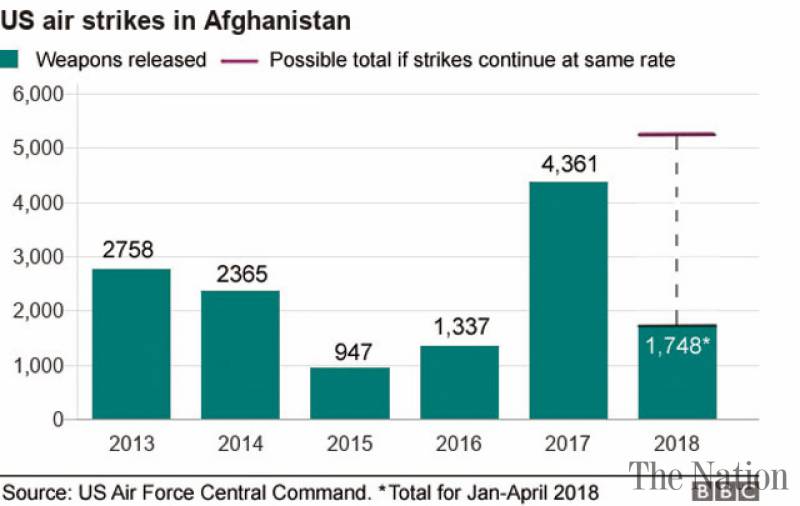

Since President Trump announced his Afghanistan strategy and committed more troops to the conflict last August, the number of bombs dropped by the US Air Force has surged dramatically. New rules of engagement have made it easier for US forces to carry out strikes against the Taliban, and resources have shifted to Afghanistan as the fight against the Islamic State group in Syria and Iraq winds down.

Heavy bombing against the Taliban and IS saw more Afghan civilians killed and injured from the air in 2017 than at any time since the UN began counting in 2009. In the first quarter of this year – before the Dasht-e-Archi incident – 67 people were killed and 75 injured by the strikes, more than half of them women and children. There was no let-up in the bombardment even during the bitter Afghan winter, a time when fighting usually draws down before picking up again in the spring. At the same time, the US has launched a five-year plan to massively expand and overhaul the Afghan Air Force, including providing it with 159 Black Hawk helicopters. John W Nicholson, the top US general in Afghanistan, has pledged that a “tidal wave of air power” will be unleashed.

The aim of this air barrage, analysts say, is to try to push the Taliban to the negotiating table, and perhaps bring an end to America’s longest war – which has dragged on for 17 years. But when helicopters mow down children at a religious ceremony, as in Dasht-e-Archi, it raises significant questions for both Washington and Kabul, and supplies potent propaganda for the Taliban.

Although the Afghan government said the strikes targeted senior Taliban leaders planning an attack on Kunduz city, “those helicopter pilots must have seen the children”, says Kate Clark of the Kabul-based Afghanistan Analysts Network. “You can’t attack an open-air gathering in a helicopter and not see who you are going to kill.”

A grim conclusion, she added, is the possibility that the Afghan Air Force did not see those particular civilians as “their people”.

In a 5 June report, the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission said the attack was a “war crime”.

In a 5 June report, the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission said the attack was a “war crime”.

After initially denying that civilians had been killed, the Afghan government eventually apologised well over a month later and offered compensation to victims’ families. It has announced an investigation. “The key difference between the government and insurgents is that a legitimate government will always seek forgiveness for mistakes,” President Ashraf Ghani said.

Activists say the US also bears responsibility for such attacks carried out by Afghan air forces. “They train the pilots, the controllers, and they provide all the equipment,” said Patricia Gossman, the senior Afghanistan researcher at Human Rights Watch.

The Nato mission in Afghanistan, Resolute Support, said US and international forces had “no involvement” in the 2 April attack. While advisers “assist in the development of doctrine that guides the Afghan Air Force decision-making process”, a spokesperson said, they are not involved in decision-making for Afghan mission planning or targeting,

The spokesperson added: “Both the Afghan Air Force and US Forces-Afghanistan adhere to the International Laws of Armed Conflict. We constantly reiterate the importance of minimising civilian casualties, from operational planning, to targeting, to execution.

“Distinguishing military targets from civilian persons, limiting collateral damage, and using only proportional force are all assessed and applied prior to each strike.”

But Afghan forces are not the only ones that make mistakes: US bombs killed at least 154 civilians in 2017, according to the UN mission in Afghanistan, while the Afghan Air Force killed 99.

Observers say that about a decade ago international forces made a concerted effort to bring down civilian casualties from air strikes. Then Afghan President Hamid Karzai was a strident critic of US bombings, decrying them as violations of Afghanistan’s sovereignty.

“They had a dedicated Civilian Casualty mitigation team that analysed each incident, they had people who made site visits,” said Ms Gossman. “Since 2014, the Civilian Casualties Team at Resolute Support is much smaller, they don’t do site visits. They don’t talk to victims, witnesses or other local sources like medical personnel.”

Resolute Support says it and the US military only investigate allegations of civilian casualties from their own actions. Those investigations may include site visits if it safe to do so and “if reasonably available information is insufficient to confirm or disprove the allegation”.

Most civilian casualties in Afghanistan are still caused by anti-government groups like the Taliban and IS and, despite the heavy bombing, it does not appear that the US has become more careless in its approach to protecting civilians. The total number of weapons dropped by the US Air Force increased by 226% from 2016 to 2017, while over the same period, civilian casualties from Afghan and US air strikes rose by 7%.

Total civilian casualties from all sources actually decreased slightly, driven in particular by a lower toll from ground offensives. So although more civilians died in air attacks, it looks like the increased air cover may have prevented the Taliban from mounting major assaults on population centres, says Kate Clark.

In any case, the Dasht-e-Archi incident should be “a wake-up call for the government, people in charge of the air force and the US trainers”, she said.

Others believe that the entire strategy of pounding the Taliban militarily is misguided. A recent BBC study found that Taliban fighters are openly active in 70% of Afghanistan.

Barnett Rubin, who served as senior adviser to the Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan at the US Department of State from 2009-2013, said the air campaign was having “no strategic effect”.

“They are just fighting the same war over for the 17th time,” said Mr Rubin, who argues that a consensus between Afghanistan’s neighbours and the major powers is a pre-requisite to creating a stable Afghanistan.

The current situation “is an irreversible stalemate”, he said, adding that if it changes “in the medium to long-term, it will only change against us.”–BBC

Originally Published in Daily The Nation