Problematizing the Category of “Sex” Queer Theory | CSS Gender Studies Notes

Queer Theory

One is not born a woman, but rather becomes one.

—Simone de Beauvoir

The origin of uncomfortable conversations draw attention of individuals towards the real myth behind the Queer theory that has been a glaring topic in the community since its inception. The conceptual framework is not only stuck with the issues as per the required plan of action in the way. The anthology that focuses on the various debates are the best by product with other concepts as society needs. Many debates and topics has been introduced in the manner that exactly required to initiate the way in respective manner.

The important issues that has been a debate regarding the elements as the intimacy, privacy and even as the sex harassment that has been a normal topic to discuss with all formalities. The concept initialization regarding the sex and even the other elements in the gender studies are not the product of abrupt decision in gender studies. Oppositely, it has been an issue since the inception of gender and conception of gender linkage with the society. There are possible four major institutions in the society and these institutions always handles the matter of gender that has been using as the Queer theory with the same pace as the gender understand.

Queer Theory

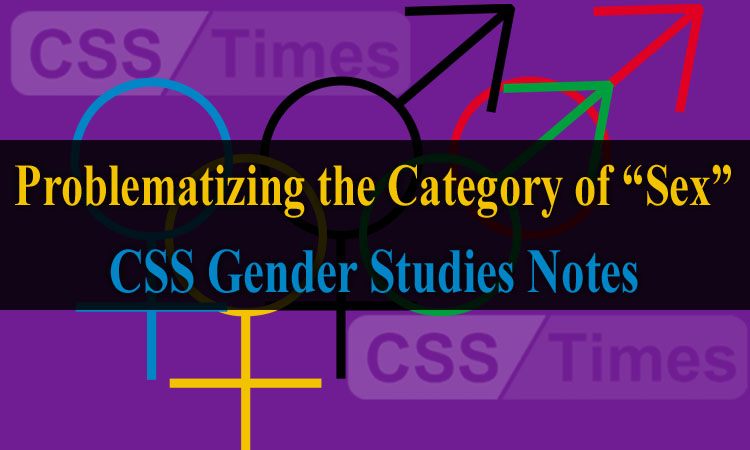

Queer Theory is a perspective that problematizes the manner in which we have been taught to think about sexual orientation. By calling their discipline “queer,” these scholars are rejecting the effects of labeling; instead, they embrace the word “queer” and have reclaimed it for their own purposes. Queer theorists reject the dichotomization of sexual orientations into two mutually exclusive outcomes, homosexual or heterosexual. Rather, the perspective highlights the need for a more flexible and fluid conceptualization of sexuality—one that allows for change, negotiation, and freedom. The current schema used to classify individuals as either “heterosexual” or “homosexual” pits one orientation against the other. This mirrors other oppressive schemas in our culture, especially those surrounding gender and race (black versus white, male versus female).

Queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick argued against American society’s monolithic definition of sexuality—against its reduction to a single factor: the sex of one’s desired partner. Sedgwick identified dozens of other ways in which people’s sexualities were different, such as:

Check Also: Gender Studies MCQs

- Even identical genital acts mean very different things to different people.

- Sexuality makes up a large share of the self-perceived identity of some people, a small share of others’.

- Some people spend a lot of time thinking about sex, others little.

- Some people like to have a lot of sex, others little or none.

- Many people have their richest mental/emotional involvement with sexual acts that they don’t do, or don’t even want to do.

- Some people like spontaneous sexual scenes, others like highly scripted ones, others like spontaneous-sounding ones that are nonetheless totally predictable.

- Some people, homo- hetero- and bisexual, experience their sexuality as deeply embedded in a matrix of gender meanings and gender differentials. Others of each sexuality do not

- In the end, queer theory strives to question the ways society perceives and experiences sex, gender, and sexuality, opening the door to new scholarly understanding.

Once the term ‘queer’ was, at best, slang for homosexual, at worst, a term of homophobic abuse. In recent years ‘queer’ has come to be used differently, sometimes as an umbrella term for a coalition of culturally marginal sexual self-identifications and at other times to describe a nascent theoretical model which has developed out of more traditional lesbian and gay studies. The rapid development and consolidation of lesbian and gay studies in universities in the 1990s is paralleled by an increasing deployment of the term ‘queer’. As queer is unaligned with any specific identity category, it has the potential to be annexed profitably to any number of discussions. In the history of disciplinary formations, lesbian and gay studies are itself a relatively recent construction and queer theory can be seen as its latest institutional transformation.

Broadly speaking, queer describes those gestures or analytical models which dramatize incoherencies in the allegedly stable relations between chromosomal sex, gender and sexual desire. Resisting that model of stability–which claims heterosexuality as its origin, when it is more properly its effect–queer focuses on mismatches between sex, gender and desire. Institutionally, queer has been associated most prominently with lesbian and gay subjects, but its analytic framework also includes such topics as cross-dressing, hermaphroditism, gender ambiguity and gender-corrective surgery.

(Hermaphroditism, also called intersex, is a disorder involving sexual development.)

Whether as transvestite performance or academic deconstruction, queer locates and exploits the incoherencies in those three terms which stabilize heterosexuality. Demonstrating the impossibility of any ‘natural’ sexuality, it calls into question even such apparently unproblematic terms as ‘man’ and ‘woman’.

The recent intervention of this confrontational word ‘queer’ in altogether politer academic discourses suggests that traditional models have been ruptured. Yet its appearance also marks continuity. Queer theory’s debunking of stable sexes, genders and sexualities develops out of a specifically lesbian and gay reworking of the post-structuralist figuring of identity as a constellation of multiple and unstable positions. Queer is not always seen, however, as an acceptable elaboration of or shorthand for ‘lesbian and gay’. Although many theorists welcome queer as ‘another discursive horizon, another way of thinking the sexual’ others question its efficacy. The most commonly voiced anxieties are provoked by such issues as whether a generic masculinity may be reinstalled at the heart of the ostensibly gender-neutral queer; whether queer’s transcendent disregard for dominant systems of gender fails to consider the material conditions of the west in the late twentieth century; whether queer simply replicates, with a kind of historical amnesia, the stances and demands of an earlier gay liberation; and whether, because its constituency is almost unlimited, queer includes identificatory categories whose politics are less progressive than those of the lesbian and gay populations with which they are aligned.

Whatever ambivalences structure queer, there is no doubt that its recent redeployment is making a substantial impact on lesbian and gay studies. Yet, almost as soon as queer established market dominance as a diacritical term, and certainly before consolidating itself in any easy vernacular sense, some theorists are already suggesting that its moment had passed and that ‘queer politics may, by now, have outlived its political usefulness’. 2 Does queer become defunct the moment it is an intelligible and widely disseminated term? Teresa de Lauretis, the theorist often credited with inaugurating the phrase ‘queer theory’, abandoned it barely three years later, on the grounds that it had been taken over by those mainstream forces and institutions it was coined to resist.

Explaining her choice of terminology in The Practice of Love: Lesbian Sexuality and Perverse Desire (1994), de Lauretis writes: “As for ‘queer theory’, my insistent specification lesbian may well be taken as a taking of distance from what, since I proposed it as a working hypothesis for lesbian and gay studies in this very journal has very quickly become a conceptually vacuous creature of the publishing industry’. Distancing herself from her earlier advocacy of queer, de Lauretis now represents it as devoid of the political or critical acumen she once thought it promised.

In some quarters and in some enunciations, no doubt, queer does little more than function as shorthand for the unwieldy lesbian and gay, or offer itself as a new solidification of identity, by kitting out more fashionably an otherwise unreconstructed sexual essentialism. Certainly, ‘it’s sudden and often uncritical adoption has at times foreclosed what is potentially most significant–and necessary–about the term’ Queer retains, however, a conceptually unique potential as a necessarily unfixed site of engagement and contestation. Admittedly not discernible in every mobilization of queer, this constitutes an alternative to de Lauretis’s narrative of disillusionment. Judith Butler does not try to anticipate exactly how queer will continue to challenge normative structures and discourses. On the contrary, she argues that what makes queer so efficacious is the way in which it understands the effects of its interventions are not singular and therefore cannot be anticipated in advance. Butler understands, as de Lauretis did when initially promoting queer over lesbian and gay that the conservative effects of identity classifications lie in their ability to naturalize themselves as self-evident descriptive categories. She argues that if queer is to avoid simply replicating the normative claims of earlier lesbian and gay formations, it must be conceived as a category in constant formation:

[It] will have to remain that which is, in the present, never fully owned, but always and only redeployed, twisted, queered from a prior usage and in the direction of urgent and expanding political purposes, and perhaps also yielded in favor of terms that do that political work more effectively

In stressing the partial, flexible and responsive nature of queer, Butler offers a corrective to those naturalized and seemingly self-evident categories of identification that constitute traditional formations of identity politics. She specifies the ways in which the logic of identity politics–which is to gather together similar subjects so that they can achieve shared aims by mobilizing a minority-rights discourse-is far from natural or self-evident.

In the sense that Butler outlines the queer project–that is, to the extent that she argues there can’t be one–queer may be thought of as activating an identity politics so attuned to the constraining effects of naming, of delineating a foundational category which precedes and underwrites political intervention, that it may better be understood as promoting a non-identity–or even anti-identity–politics. If a potentially infinite coalition of sexual identities, practices, discourses and sites might be identified as queer, what it betokens is not so much liberal pluralism as a negotiation of the very concept of identity itself. For queer is, in part, a response to perceived limitations in the liberationist and identity-conscious politics of the gay and lesbian feminist movements. The rhetoric of both has been structured predominantly around self-recognition, community and shared identity; inevitably, if inadvertently, both movements have also resulted in exclusions, delegitimation (countable and uncountable, plural delegitimations), and a false sense of universality. The discursive proliferation of queer has been enabled in part by the knowledge that identities are fictitious–that is, produced by and productive of material effects but nevertheless arbitrary, contingent and ideologically motivated.

Unlike those identity categories labeled lesbian or gay, queer has developed out of the theorizing of often unexamined constraints in traditional identity politics. Consequently, queer has been produced largely outside the registers of recognition, truthfulness and self-identity.

Queer, then, is an identity category that has no interest in consolidating or even stabilizing itself. It maintains its critique of identity-focused movements by understanding that even the formation of its own coalitional and negotiated constituencies may well result in exclusionary and reifying effects far in excess of those intended.

Acknowledging the inevitable violence of identity politics and having no stake in its own hegemony, queer is less an identity than a critique of identity. But it is in no position to imagine itself outside that circuit of problems energized by identity politics. Instead of defending itself against those criticisms that its operations inevitably attract, queer allows such criticisms to shape it’s–for now unimaginable–future directions. ‘The term’, writes Butler, ‘will be revised, dispelled, rendered obsolete to the extent that it yields to the demands which resist the term precisely because of the exclusions by which it is mobilized’. The mobilization of queer–no less than the critique of it–foregrounds the conditions of political representation: its intentions and effects, its resistance to and recovery by the existing networks of power.

For Halperin, as for Butler, queer is a way of pointing ahead without knowing for certain what to point at. “‘Queer” … does not designate a class of already objectified pathologies or perversions’, writes Halperin “rather, it describes a horizon of possibility whose precise extent and heterogeneous scope cannot in principle be delimited in advance”. Queer is always an identity under construction, a site of permanent becoming: “utopia in its negativity, queer theory curves endlessly toward a realization that its realization remains impossible” The extent to which different theorists have emphasized the unknown potential of queer suggests that its most enabling characteristic may well be its potential for looking forward without anticipating the future. Instead of theorizing queer in terms of its opposition to identity politics, it is more accurate to represent it as ceaselessly interrogating both the preconditions of identity and its effects. Queer is not outside the magnetic field of identity. Like some postmodern architecture, it turns identity inside out, and displays its supports exoskeletally. If the dialogue between queer and more traditional identity formations is sometimes fraught–which it is–that is not because they have nothing in common. Rather, lesbian and gay faith in the authenticity or even political efficacy of identity categories and the queer suspension of all such classifications energize each other, offering in the 1990s–and who can say beyond?–the ambivalent reassurance of an unimaginable future.

Check Other NOTES for Gender Studies

- Gender Studies Handwritten Notes (Download in PDF) | Types of Feminism

- Gender Studies Short Q/A | (Deconstruction of Cultural and Structural Forms of Violence)

- Gender Studies | Problematizing the Category of “Sex” Queer Theory

- The Development of Social Construction of Gender | CSS Gender Studies Notes

- Understanding the Social Construction of Gender | CSS Gender Studies Notes

- Social Construction of Gender | CSS Gender Studies Notes

- Gender Studies Notes | Theories of Social Construction of Gender